This source is a study done by the RAND Corporation in which they measured the effectiveness of various methods of controlling cocaine. In the report, the authors measure source control, interdiction, domestic enforcement, and treatment of users, trying to evaluate which of these methods will be most effective at reducing the prevalence of cocaine. The report found that the most cost effective method of dealing with cocaine was to increase treatment to 100% and cut supply controls by 25%. Furthermore, they found long term consumption would decrease the most if the government were to increase treatment to 100% and maintain its supply controls. This was counter to much of the logic of Washington during that time, as many believed making cocaine more expensive would reduce use, but RAND found it would be much cheaper and easier to just reduce demand at home.

I decided to look into this source after I heard about it from two other sources. First, it is brought up in Livingstone’s book as a possible alternative to Plan Colombia and it was also mentioned by Senator Wellstone in his interview on PBS. This source is important because it gives credence to the argument that controlling demand is more important than controlling supply. Both Wellstone and Livingstone mentioned this, they are both known to be critical of the war on drugs. RAND on the other hand, is an organization that consults the government on a matter of policies and issues which would in theory give them some more legitimacy in the government. The fact that this approach was so ignored as the U.S. embarked on spending over $1.3 billion in its first round of funding for Plan Colombia, explains a lot about the politics of fighting drugs.

Transcript:

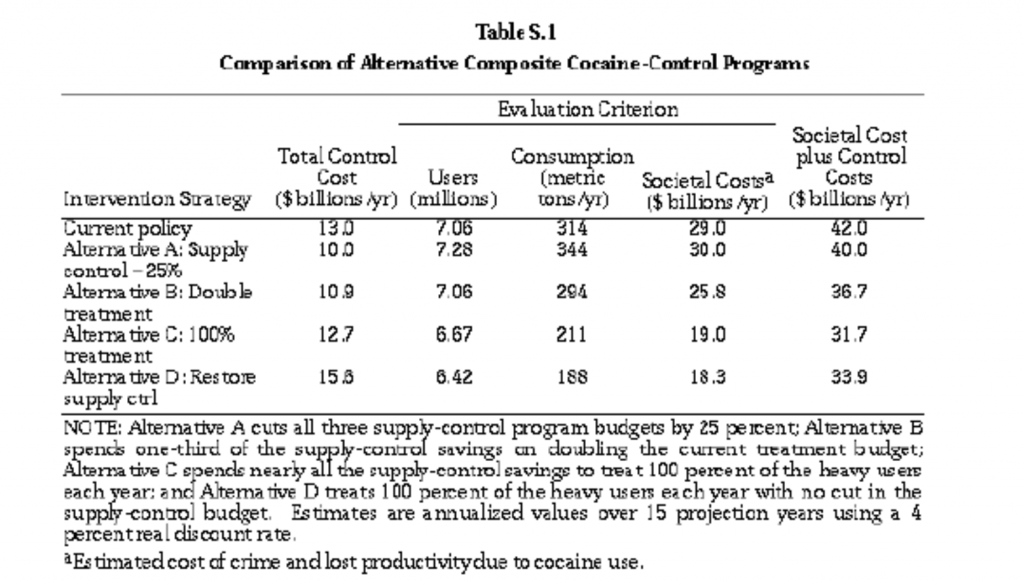

Finally, treating all heavy users without changing the current budget for supply control would decrease user counts, annual consumption, and societal costs even more. However, restoring the supply-control budget would increase control costs more than it would decrease societal costs, so the total annual saving relative to current policy, $8.1 billion, would be less than that under Alternative C.

Hence, this report concludes that treatment of heavy users is more cost-effective than supply-control programs. One might wonder how this squares with the (dubious) conventional wisdom that, with treatment, “nothing works.” There are two explanations. First, evaluations of treatment typically measure the proportion of people who no longer use drugs at some point after completing treatment; they tend to underappreciate the benefits of keeping people off drugs while they are in treatment–roughly one-fifth of the consumption reduction generated by treatment accrues during treatment. Second, about three-fifths of the users who start treatment stay in their program less than three months. Because such incomplete treatments do not substantially reduce consumption, they make treatment look weak by traditional criteria. However, they do not cost much, so they do not dilute the cost-effectiveness of completed treatments.

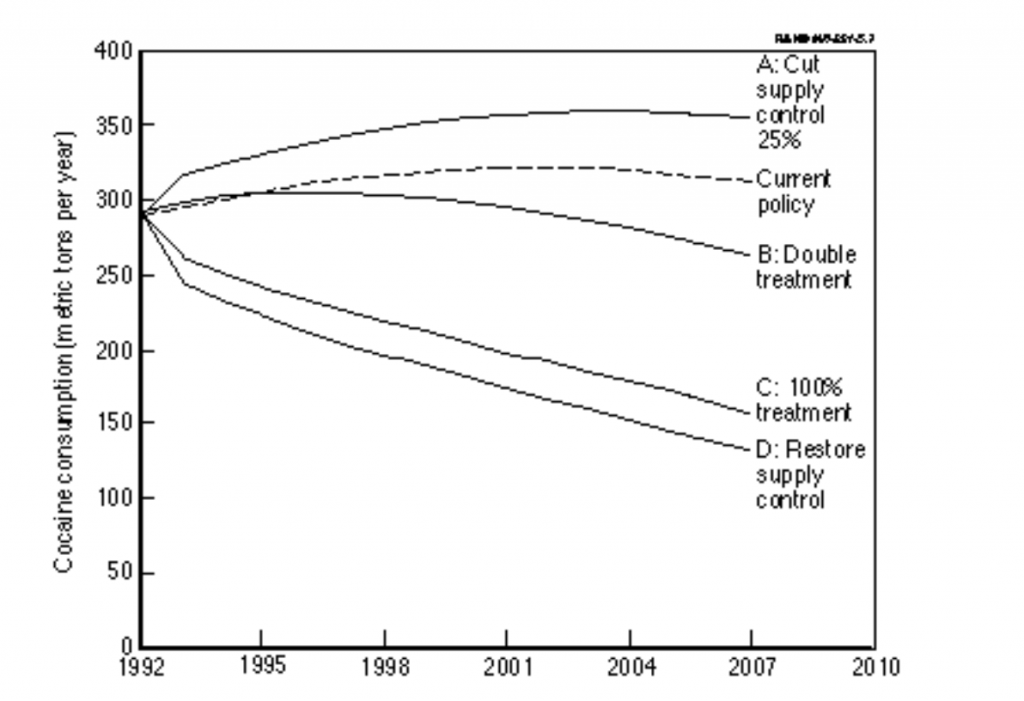

Does this mean that treatment is a panacea? Unfortunately not, because there is a limit on how much treatment can be done. In our analysis, we explore the consequences of treating every heavy user once each year (Alternatives C and D). In principle, even more treatment is possible because the average duration of a treatment is less than 12 months. However, considering the difficulties of getting people into treatment, more treatment may not be feasible. Treating all heavy users once each year would reduce U.S. consumption of cocaine by half in 2007, and by less than half in earlier years (see Figure S.7).

Rydell, C. Peter, and Susan F. Everingham. “Controlling Cocaine: Supply Versus Demand Programs.” Rand.org. RAND Corporation, May 26, 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20060526084433/http://www.fathom.com/media/PDF/2184_cocainess.pdf.